Subscribe to Blog via Email

Good Stats Bad Stats

Search Text

April 2025 S M T W T F S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 -

Recent Posts

Good Stats Bad Stats

goodstatsbadstats.com

Statistics and the Australian Open

I watched parts of the Federer-Tsonga match in the Australian Open a couple of days ago. Federer won the first set of the match. At that point the announcers started a discussion of the players with the highest winning percentage for a match given that the player had won the first set of the match. After a bit of back and forth between the two announcers they displayed the graphic on the right.

I watched parts of the Federer-Tsonga match in the Australian Open a couple of days ago. Federer won the first set of the match. At that point the announcers started a discussion of the players with the highest winning percentage for a match given that the player had won the first set of the match. After a bit of back and forth between the two announcers they displayed the graphic on the right.

One major glitch in the graphic is that ESPN failed to properly understand what a percent is. Reading the graphic as it is presented Federer has less than a one percent chance of winning a match if he wins the first set. The error – a misplaced decimal point. Federer’s actual record was 781 wins and 56 loses, or 93.3 percent.

The announcers led into the discussion noting that the statistic was representative of the then current situation in the match with Federer having beaten Tsonga in the first set. The statistic represents Federer’s record in all matches. That number is not likely to be representative of his chance of winning against a player of the caliber of Tsonga who is currently ranked number eight in the world.

There is an issue with the comparability of these records across players. We all like to look at the players and say one is better than the other. But is must be realized that the these records are based on somewhere between 400 and 1100 matches. At that level if Federer had won one additional match,out of 800, he would be ranked ahead of McEnroe. So while McEnroe is ranked number five and Federer is ranked number six. The difference is largely meaningless. The order would have changed if Federer had won just one of the 56 matches he lost or if McEnroe had lost just one of the 775 matches he won.

A final question is how impressive are these records. Over ninety three percent win rates certainly seems very impressive. However to win a match after winning the first set the player only needs to win two of the following three sets. Do the math. With only a fifty percent chance of winning a set the player who has won the first set has a 69 percent chance of wining the match. What does it take to get to a 93 percent chance of winning the match? As it turns out the player only needs about a 73 percent change of winning a set. Considering that these records are compiled over opponents of all calibers, that Federer and others have been able to achieve a 93 percent win percentage seems will within what would be expected.

Record Lows on the Mississippi River

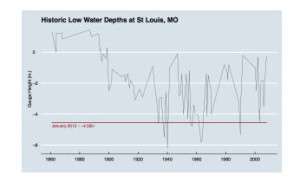

Recent news accounts (here, here, and here) have focused on the low water levels along the Mississippi River, the removal of bedrock from the river bottom, and the impact on barge traffic along the river south of St. Louis. A post over at rud.is asked “How Low Can It [The Mississippi River] Go?” The graphic accompanying the post caught my attention.  The author posted a full size pdf file here.

The author posted a full size pdf file here.

There are a couple of problems with the graphic. There are also problems with the source data set used in the graphic.

Lessons to learn are that not only must the analyst produce a quality graph but underlying data must be examined closely.

First the issues I have are with the graph. First the annotations on the graph give the gauge levels in inches. The actual levels are in feet. The bigger issue is with the type of graph used for the data set. The underlying data is a file record lows available from NOAA and the USGS. They provide a link to the list of records, daily and historical data on river levels and flow at St. Louis at the source website. However the author of the blog posting graphed the data as if it were a time series. In treating it as a time series he says:

As you can see, there have only been four other (recorded) times when the river was this low and it has just come off of multi-year severely high points with a fairly rapid trend downwards.

His confusion on the type of graph he shows is apparent in his count of the number of times the the low as less than current levels. He cites four instances, but looking at the graphic it is clear that there are not four but eight such instances. Because consecutive record lows on the time scale are neighboring points he seems to be counting them as just one low.

A more appropriate plot would be an x-y plot with the the x-axis listing record lows and the y-axis showing the level for each of these lows. The time spread could still be shown on the x-axis. The error the author made was to join the point and create a line plot. An even more useful plot would be one showing annual low levels along the river. This could be a true line chart.

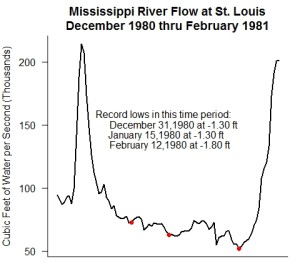

What the author also failed to do was look closely at the data he was using.  The data file lists 84 record lows since 1861. A key question is how the term record low defined in the data set. At first glance the data set seems to have be constructed by computing monthly low river levels and selecting the lowest 84 values. This becomes apparent when one looks at the data for December 1980 thru February 1981 where there are three record lows in the data set. A graph of the flow levels of the river is shown at the right with the three record lows marked by red dots. (The graph shows flow rates and not river levels. This is because the USSG website provides flows and not gauge readings for 1980.) The graph shows a mostly steady downward trend in the rive level from mid December into February. It would more appropriate, for data analysis purposes to reflect only one record low in the record. It is not clear to me why the USGS and NOAA choose a different approach. There is one exception to this apparent rule that is very hard to explain. In 1970 the file shows a record low of -2.60 feet on January 19th, and a record low of -4.00 feet on the next day – January 20th. I don’t know why back to back days would be recorded as record lows, nor do I think that the river level dropped 1.4 feet in one day. I suspect a typo in the file. In fact the flow data in the NSGS file show a flow of 57.2 kilo cubic feet per second on the 19th and 57.4 on the 20th.

The data file lists 84 record lows since 1861. A key question is how the term record low defined in the data set. At first glance the data set seems to have be constructed by computing monthly low river levels and selecting the lowest 84 values. This becomes apparent when one looks at the data for December 1980 thru February 1981 where there are three record lows in the data set. A graph of the flow levels of the river is shown at the right with the three record lows marked by red dots. (The graph shows flow rates and not river levels. This is because the USSG website provides flows and not gauge readings for 1980.) The graph shows a mostly steady downward trend in the rive level from mid December into February. It would more appropriate, for data analysis purposes to reflect only one record low in the record. It is not clear to me why the USGS and NOAA choose a different approach. There is one exception to this apparent rule that is very hard to explain. In 1970 the file shows a record low of -2.60 feet on January 19th, and a record low of -4.00 feet on the next day – January 20th. I don’t know why back to back days would be recorded as record lows, nor do I think that the river level dropped 1.4 feet in one day. I suspect a typo in the file. In fact the flow data in the NSGS file show a flow of 57.2 kilo cubic feet per second on the 19th and 57.4 on the 20th.

Given these issues I would prefer that a graph of river levels showing the low levels that occur be a time series of the annual levels. Reviewing the data over the 150 year time period, and the tables provided by the USGA and NOAA it is clear that the river has clear seasonal variations with the lowest levels occurring during the winter months. With that in mind I would create an annual measure for the period from July 1 to June 30 and plot those values.

The take home points here are to be careful when plotting data and examine the data very carefully prior to using it. Key questions are is the data of sufficient quality and is it appropriate for the uses being made of it.

Posted in Data Quality, Graphics Visualization, Methodolgy Issues

Some records are not worth talking about

I tend to dislike it when the local weather station reports a new record. There are just so many categories of data that the weather service track. In most places data exists for a maximum of only 100 to 150 years. There are record highs, record lows, record low highs, record high lows, record rainfall, and on an on. It is almost possible to report a new record every day of the year.

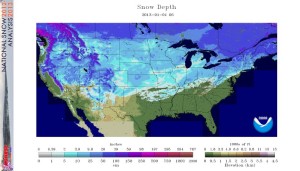

But AccuWeather.com has set a new standard. They recently reported “January 1 Snow Coverage Sets New Record for the United States.” But read on. The previous record was set in 2010.

But AccuWeather.com has set a new standard. They recently reported “January 1 Snow Coverage Sets New Record for the United States.” But read on. The previous record was set in 2010.

Now perhaps it was a slow news day on January 4th when they published this piece. But I must say give me a break. The records only go back ten years. This is data that NOAA releases each day. With just ten years of data one can expect that a new daily record will be set three times in a month. And that is just an average. Is this really news?

But AccuwWeather goes on. They then tell me that snow cover “increased dramatically” between December 1st and January 1st. What did they expect? Isn’t this the norm? After all there has been an additional month for the temperatures to get colder with the onset of winter and more time for snow to accumulate.

Posted in Statistical Literacy