Subscribe to Blog via Email

Good Stats Bad Stats

Search Text

April 2025 S M T W T F S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 -

Recent Posts

Good Stats Bad Stats

goodstatsbadstats.com

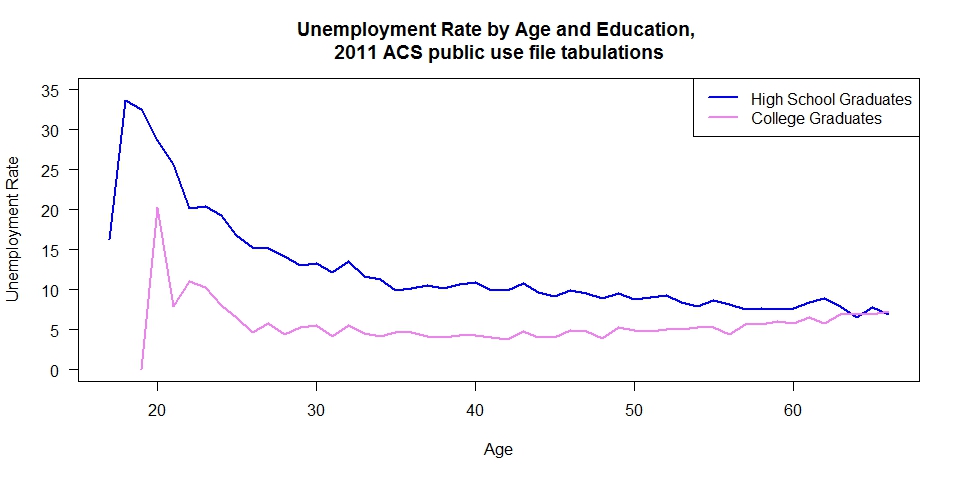

Education and Unemployment

I posted earlier today on the issue of education and unemployment. In that post I suggested the a plot of the unemployment rate vs age by education would be a better plot than the one shown over at Calculated Risk. The plot above show that data based on calculations I did today using the 2011 public use files for the American Community Survey.

I posted earlier today on the issue of education and unemployment. In that post I suggested the a plot of the unemployment rate vs age by education would be a better plot than the one shown over at Calculated Risk. The plot above show that data based on calculations I did today using the 2011 public use files for the American Community Survey.

In order to keep the concepts simple there are only two groups shown. The line is blue is the rate for those with only a regular high school diploma. I did not include those who have earned a GED or those who went on to get at least a partial college education. I did not include either those currently enrolled in school. Similarly for the college graduates I included only those with a college degree. I excluded those with advanced degrees and those currently enrolled in school. Thus the comparison is strictly focused on the advantage of of college degree as opposed to a high school diploma.

The graph shows the unemployment rate by singe year of age starting at age 16 and going up to age 66. It clearly shows that at all age levels those with a college degree hold a clear advantage over those with just a high school diploma by several percentage points during most of their working life. It is not until age 45 that the difference in unemployment rates drops below five percentage points.

Thus from the employment perspective there is every incentive to go on and get the college degree.

Some limitations still apply. The plot is focused in the middle of the present recession and thus the advantage may not be as great during the boom years. Also the advantage is very likely a function of the field of study for the college degree.

The next project will be to start looking at the income data out of the American Community Survey. Had I realized how easy it would be to create the plot above I would have gone ahead and done the work needed to include it in my first post on the subject.

Posted in Methodolgy Issues, Telling the Full Story, Where's the Data?

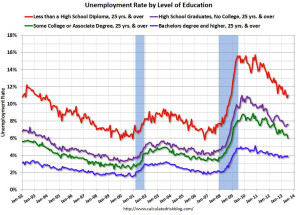

Do we need more college graduates?

Last week, after the release of the most recent jobs report by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the Calculated Risk blog posted the image at the right showing the unemployment rate over the last twenty years by level of education for those age 25 and over. Bill made four comments about the graphic.

Last week, after the release of the most recent jobs report by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the Calculated Risk blog posted the image at the right showing the unemployment rate over the last twenty years by level of education for those age 25 and over. Bill made four comments about the graphic.

Although education matters for the unemployment rate, it doesn’t appear to matter as far as finding new employment – and the unemployment rate is moving sideways for those with a college degree!

Note: This says nothing about the quality of jobs – as an example, a college graduate working at minimum wage would be considered “employed”.

The observation that education matters is clearly true. Also true is his statement that the graphic says nothing about the quality of the jobs. The claim that the unemployment rate is moving sideways for those with a college degree can be argued. The rate does seem to have leveled off in the last year. However the graphic says nothing about finding new employment. It is just simply the wrong set of data to answer any questions about finding a new job.

Meanwhile this week Kaiser over at junkcharts picked up on the Calculated Risk post and made some very good points in his elaborations. After recognizing that the chart is for those age 25 and over he says:

The low unemployment rate for all college graduates masks the challenging job market for recent college graduates. The misinterpretation of this chart leads to wrongheaded policies such as make more college graduates.

Actually the chart does not really mask the situation for new grads as most of them are not yet age 25. The real problem here is that we do not have the data for recent grads at hand in either of these two posts. Kaiser is right however in telling us that using this graphic does lead some to say we need more college grads. Again the graphic and the data in includes is not at all informative in addressing the question of the wisdom of spending money and going into debt to pay for college.

At the end of his post Kaiser says

The solution then is to create your own fine print. Spend inordinate amounts of time understanding how data is collected. Dig deeply into how data is defined.

No, this work is not sexy. (PS. If you can’t stand it, you really shouldn’t be in data science.)

This is exactly what is needs to be done here.

In a two years ago on employment and education Kaiser said:

If the market is not clearing now for new college graduates, encouraging more kids to get college degrees will only worsen the unemployment rate for new college grads. It will also drive down starting salaries for new college graduates. It will also stick many more of our kids with heavy education debt.

Part of what needs to be considered here are the alternatives. This is not just a question of what happens to the recent college graduates, but also of what happens to those who elect not to go to college. Students have the choice of the two paths. They can take one and bear the costs of not taking the alternative.

There is data available on the subject. The BLS periodically releases reports on employment for both recent high school and recent college graduates. In a report earlier this year they cited an unemployment rate for recent college graduates of 13.6 percent. Unfortunately they define recent as ages 20 to 29. To my way of thinking that is too broad a category. I would like to see single year age groups. Also this past April the BLS released a report on the employment status of recent high school graduates. In that report they cite an unemployment rate of 34.4 percent. This was for those who graduated between January and October 2012 and who were not enrolled in college. This is why we need the single year data for the college graduates. On the surface it appears that a person graduating from college has the choice of a 34 percent unemployment rate, or going the college and facing an unemployment rate much lower, but also accumulating some debt to pay for that college education. This is where it gets more complicated as there is data out there that shows that lifetime earnings for college graduates is much higher that for high school graduates.

The issue of how many college graduates we need in this country is not a new one. Questions about salary depression due to “too many college graduates” are not a new one. Questions about college graduates taking jobs requiring only a high school diploma are not new. They have been around since the 1970’s. Two papers released by the BLS in the 1990’s are relevant to the discussion and can be found here and here. The firs to these two paper starts with the question “If as some analysts contend, the rising relative wages of college students in the 1980’s suggest a shortage of these workers, why did one-fifth of them accept jobs that traditionally do not require a degree for entry?”

At the end of his post Kaiser adds:

In data, there is often no fine print to be found. In Big Data, this problem is aggravated by a thousand times. Unfortunately, magnifying blank is still blank. So, having the magnifying glass is not enough.

The solution then is to create your own fine print. Spend inordinate amounts of time understanding how data is collected. Dig deeply into how data is defined.

No, this work is not sexy. (PS. If you can’t stand it, you really shouldn’t be in data science.)

Looking at other research that has already been done and other sources of data that are available is a big part of the work he is referring to. Also part of that work is creating your own tabuations and graphics from the raw data. Let me suggest that the data in the American Community Survey (ACS) could be very useful here. This survey conducted by the Census Bureau is the replacement for the long form in the decennial census. It is a very large set of data. Included is information on education, income, and employment. It should be possible to look at data on the unemployment rate for both college graduates and high school graduates by single year of age. (The definition of unemployment used in the ACS is not quite the same as the official measure used in the Current Population Survey by the BLS, but those differences should not create any significant problems in the analysis.) Combining the unemployment data with the education and income data can also provide a picture of how much income is impacted. Further work can be done by tracking the data over a number of years using the ACS data. If I can swing some free time I’ll play around with the data. I do enjoy playing with data.

What I envision are two plots. One would show unemployment rate by single year of age. The second would show per capita income by single year of age. I would have two groups. College graduates only who are not enrolled in school would be one group. The second would be high school graduates who are not enrolled in school.

This data only gets an income and employment. It will not address the question of do we have too many college graduates. Remember though that the individual choice is to maximize their earnings. So if getting a college degree lowers everyone’s income they are better off it getting the degree increases their own income over what they would have earned if they had chosen not to go to college. Somehow the cost of the college education and the lack of earnings while in college need to be factored into their calculations. The question of the number of college degrees is a societal question that the individual trying to maximize their own earnings is less concerned with.

Posted in Where's the Data?

Breastfeeding will………..

Two studies have been in the news recently touting the benefits of breastfeeding. The first linked breastfeeding to improved intelligence for the child. The second study claimed that the breastfeeding may reduce the risk for Alzheimer’s.

The full paper on the link between IQ and breast feeding is not available online. However the abstract can be viewed here. There are two key measures provided in the abstract to the paper. The first claimed

longer breastfeeding duration was associated with higher Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test score at age 3 years (0.21; 95% CI, 0.03-0.38 points per month breastfed)

And the second claimed

higher intelligence on the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test at age 7 years (0.35; 0.16-0.53 verbal points per month breastfed; and 0.29; 0.05-0.54 nonverbal points per month breastfed).

The conclusion is that on the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test with six months of breast feeding the test score is increased somewhere between 0.18 and 2.28 points. This is a test with a standardized score of 100 with a standard deviation of 15. This means that roughly 68 percent of the population falls in the range from 85 to 115 and that roughly 95 percent of population falls in the range from 70 to 130.

Similarity for the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test the predicted improvements from the research are in the range from 0.96 to 3.18 for thee verbal test and in the range 0.30 to 3.24 for the nonverbal. This test is scaled in the same manner as is the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test.

The results then are very small. They are much smaller than is the accuracy of the tests themselves on an individual level. IQ also is not the the sole determinate of how successful one is in life – no matter how one defines success. With such small improvement is it even worth the effort to determine if the analysis methods used in the study were appropriate?

There are numerous other reasons to breastfeed. Breastfeed by all means if one can. But increasing a child’s IQ by the levels claimed in this study does not seem to me at least to rise to the top of the list.

The study on the link between breastfeeding and Alzheimer’s was based on a recall study of 81 patients age 70 or older were selected in a very nonrandom fashion. This is a very small sample size. But even with that limitation the authors were making claims based on family history of Alzheimer’s. Consider too the age of the patients when the study was conducted. They were asking mom’s how long they breast fed when they had kids likely 40-50 years earlier. That alone raises all sorts of questions about recall issues especially when they are expected to recall not only if they breastfed, but for how long they breastfed.

A good overview and evaluation of the research can be found here.

I found the real kicker in the reported results when one of the authors is cited as follows:

Also, Dr. Fox revealed to The Independent that a similar study with a large sample of several thousand women in China found the opposite: that women who breastfed for a shorter period of time were less likely develop dementia. This, Dr. Fox says, may be down to the environmental and lifestyle differences.

In short the author is saying my results contradict those of a much larger study and all I’m going to do is speculate on the reasons for the differences. I need a better answer than that if I am going to trust the conclusion of this small study.

As a final criticism, both of these papers is hidden behind a pay-wall. The amount that most of these place charge to obtain a copy of the paper is in my mind exhortation. A few pages for $30.00 or more boggles my mind. At that price the going price for a college text book should be well over $1,000. I will say again any author who ensures substantial media publicity for their research has an obligation to make the full paper freely and readily available online.

Posted in Data Quality, Methodolgy Issues, Publication Bias, The Media