Subscribe to Blog via Email

Good Stats Bad Stats

Search Text

April 2025 S M T W T F S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 -

Recent Posts

Good Stats Bad Stats

goodstatsbadstats.com

A matter of perspective

Robert Samuelson writes an opinion piece in the Washington Post each week. The latest was titled “The fat cats vs. the facts.” That was the print edition title. The digital edition was titled “Government is not beholden to the rich.” In it he seems to launch an attack on the elderly and on the poor making a case that government taxes the rich and gives to the elderly and to the poor. He uses data from the recent Congressional Budget Office report: “The Distribution of Federal Spending and Taxes in 2006.” That report looks as data from 2006, the most recently available data, on the taxes and benefits split by elderly and non-elderly and then for the non-elderly looks at the same numbers by the quintiles of the income distribution.

Not surprisingly the report finds that money flows toward the elderly and the poor. Samuelson quotes numbers from the report showing that the elderly, those over 65 receive, a net of about $13,000 from the government the poorest fifth of households receive about $12,600 while the richest fifth pay about $66,000.

But should we really be looking at elderly vs. the non-elderly. Certainly it shows the current state of affairs. However a historical perspective is need in this discussion. Over the past 100 years or so, and certainly since Roosevelt was president back in the 1930’s the US and the much of the world has moved from an culture where families took care of the elderly both in terms of health care and in terms of income to a culture where the government provides a sizable portion of that help. We have done that by taxing people when they are younger and paying them when they are older via Social Security, Medicare, and other programs.

It is this cultural shift which makes inappropriate comparisons and arguments about the differences in government taxes and payments for a 75 year old vs. those for a 50 year old. This is not a cross-sectional issue. It is rather a longitudinal issue. The question is did the current elderly beneficiary pay sufficient tax in his younger years to justify the benefits received today? The social security system and the Medicare system are in many ways an insurance policy. Everyone pays into the system. Those who survive long enough receive the benefits. So the real questions need to be: Are the taxes high enough during the working years to justify the benefits received? Is the retirement age set at a level that provides solvency to the system given the level of taxes and benefits? And are the benefits set at a level commensurate the taxing rate, the retirement age and the life expectancy of the survivors.

These questions do not pit the elderly against the non-elderly. Rather they recognize the life cycle of the individual within the system.

Some key observation need to be made. The first is that life expectancy has been increasing over time. Thus no one should expect benefits to remain constant and be paid for a longer period of time while keeping the tax rates the same. Something has to change. It can be the tax rate, the retirement age or the level of benefits. Choose your poison. With continual increase in life spans a 40 year old today can expect to collect from the system more than a current 60 year old. Adjustments for that change need to be considered. Commensurate with that and in line with Samuelson’s discussion of tax rate differences by income level it is well documented that the wealthy have a longer life expectancy than do the poor. So while the wealthy pay more in taxes they can also expect to collect benefits longer.

And finally a couple of specific comments on Samuelson’s writing are in order. I really wish he had done a better job of reading what he wrote.

He notes early in the piece:

The CBO divides the population into elderly (65 and over) and non-elderly households. They’re respectively 15 percent and 85 percent of the population.

But later he writes as if there is a problem”

The non-elderly paid almost 85 percent of taxes,…

Where is the problem? The elderly are 15 percent of the population and they pay 15 percent of the taxes?

By Samuelson’s logic that the elderly get undue benefits, I wonder what he thinks of our children as they pay essentially no taxes yet reap the lifetime benefits of the education they receive at the expense of the government.

But the one that really has me puzzled is when he writes:

Democracy’s problem is not the influence of money. It’s the influence of people.

I thought we called our democracy a government of the people, by the people, and for the people. I must assume that Samuelson does not believe in that kind of government. I wonder what kind he does believe in.

Posted in Methodolgy Issues

Cash for clunkers – what did you expect?

Back during the height of the recent recession we had the cash for clunkers where our government spent close to $3 billion dollars financing the trade in of so called “clunkers” for new cars in the hopes of providing a boost to the nation’s economy. The twofold strategy of the program was to give a boost to the auto industry where sales were lagging and at the same time to help reduce greenhouse emissions.

Earlier this month Brookings released a report “Cash for Clunkers:An Evaluation of the Car Allowance Rebate System.” Much of the discussion in the report is based on a paper from Resources for the Future titled “Evaluating “Cash for Clunkers: Program Effects on Auto Sales, Jobs, and the Environment.” Both papers make for very dry reading. They are very much factual oriented. The shortcoming of the papers if any is that is is not always clear exactly what data come from where. The worst data source was a survey of program participants that had only a 21 percent participation rate. That fact is only cited in the Brookings paper. I doubt that the data from the survey had a major impact on the findings cited in the two papers.

The main thrust of the papers was that the program did little to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and that the cost of the program for each new job created was quite high. The impact was to simply move vehicle purchases up in time. In short people bought cars in June that they otherwise, without the program would have purchased in August.

I would raise the question as to what did we expect from the program. It was set up to encourage people to trade in old cars and purchase new cars with somewhat better gas millage. It seems quite obvious that the goal was to simply move purchases up in time. Any criticism of the program on that dimension needs to be along the lines of was that movement effective. What is effective? I don’t know. Is moving purchase up six months good? Is moving them up three months good? Is moving them up a full year good? The real effect of any program of this nature is to provide a boost in jobs now while fully recognizing that we are paying the price of fewer jobs in the future. A car manufactured today for purchase today is a car not manufactured six months from now for a purchase then. Total vehicles manufactured will go up as now I am, for example, using the vehicle for nine years that I would otherwise have used for ten years. So the metric that should be used must answer the question of if the shift in vehicle purchase patterns was worth the money spent. The shift was going to happen. One should not criticize the program because there was a shift, but rather because the shift was ineffective in accomplishing the stated goals. The auto industry would argue that the program helped them where they were in dire straights due to a lack of sales. And I might add is this really any different than providing help to farmers in times of drought? Ask instead should the government be proving that help to either or both groups.

However it seemed many wanted to use the Brookings report to bash the cash for clunkers program without asking these important questions. George Will called it the “The lunacy of ‘Cash for Clunkers.’” Fox New said “Cash for Clunkers program falls short of goals to help economy, environment.” Autoblog said “Brookings Institution says Cash For Clunkers was a bust.” My favorite statement in what they had to report was

CARS did achieve its other goal of reducing the number of fuel-inefficient cars on the road, but that impact also was negligible, as the new, green, fuel-efficient cars bought within the program reportedly represented about half of a percent of all vehicles in the US.

They are really only said we got what was expected. Given that the program targeted the replacement of 700,000 cars that was only half a percent of the inventory. So the impact on overall fuel-efficiency was “negligible.” Did anyone who was thinking when the program was proposed and approved by the Congress do the math? How did they ever expect a different outcome?

Hotair.com went further saying “Cash for Clunkers a near-total failure says … the Brookings Institute.” I don’t think Brooking put it that way. The data may say it is true, but all they gave was the data. They seem to have left the dramatic statements to others.

In the interest of conflict of interest I don’t work for the auto industry and never have. I did not take advantage of the program and I did not like it when it was proposed. My reason was one of too many loopholes in the system. With two cars one an SUV and the second a fuel-efficient sub compact it would be easy to trade both cars in, the SUV for a sub-compact and the subcompact for an SUV and reap the benefits of the program.

Posted in Methodolgy Issues, The Media

Income inequaltiy – Change the list

Last summer CCN asked readers to vote for topics from a long list of social issues. The five topics with the highest vote counts were selected for future stories. This became their “Change the List” series. This week they posted the piece on income inequality titled “The most unequal place in America.”

While the issue of income inequality is well worth reporting and people disagree on the causes and implications of the current level of income inequality in the United States this piece fails to do even a credible job of incorporating statistical literacy into the analysis.

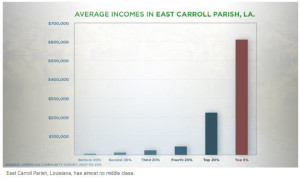

East Carroll Parish, Louisiana, with a population 7,500, was highlighted as the place with the highest level of income inequality in the United States. How was it chosen? Last fall the Census Bureau released a report using five year data from the American Community Survey where East Carroll Parish was identified as among the counties with the highest level of income inequality (see table 5). The statisticians at the Census Bureau recognized that there was enough sampling error (variance) in the estimates that they did not claim any one county was the worst. The writers at CNN thought they knew better apparently because the highest numerical estimate was for East Carroll Parish.

That is really not a major problem for the article. There is still considerable income inequality in that little Parish in LA. The bigger question is if a Parish with a population of only 7,700 and 2,500 households can represent the areas of the country with the highest level of income inequality. That means that in the graphic to the right the bar for the top 5% likely represents 50 households and is based in a sample from many fewer households. In short the actual average income could be considerably different from the numbers shown.

That is really not a major problem for the article. There is still considerable income inequality in that little Parish in LA. The bigger question is if a Parish with a population of only 7,700 and 2,500 households can represent the areas of the country with the highest level of income inequality. That means that in the graphic to the right the bar for the top 5% likely represents 50 households and is based in a sample from many fewer households. In short the actual average income could be considerably different from the numbers shown.

But there are other problems with the graph as well. First note that the six bars do not all represent the same size group. The five to the left represents 20% of the population while the final bar on the right represents only 5% of the population. That 5% overlaps with those in the fifth bar. This results in an image which shows an upward trend by cell with the change between the fifth and sixth bar being largely meaningless. It gets worst. A good graph should fully document who the data refers to. In this graphic, nor in the accompanying article are we told the group of people the average incomes refer to. Is it persons, families, or household?

The first graph in the article is titled “Level of Income Inequality.” It compares the Gini index for East Carroll Parish with that of United States, Iran, Nigeria, and Sweden. There is no explanation of why those five areas were chosen. But again it gets worst. The x-axis is labeled “Gini Index” and goes from “better” to “worst” on a scale of zero to 80. I doubt very much that an index of zero is considered better than an index of 10. A certain amount of income inequality is inevitable. While higher levels of the index are generally considered worst, the same is not true at the lower end of the scale. Also bear in mind that since the author chose to focus on the county(parish) with the highest index it was guaranteed to have an index higher than that of the United States as a whole.

Then there is the graph titled “Social Ills and Income Inequality.” The measure of “Social Ills” is undefined. But the United states stands out as the county with the highest income inequality and the worst social ills. But this is a graph of only a select subset of the developed countries in the world. Where would Iran be on this graphic? Where would Nigeria be on this graphic? What if social ills was measured based on poverty rates? What if it was measured on gender equality, what if it was measured on standards human rights? The graph itself shows a strong correlation between income inequality and the social ills index. The article tries to take this correlation and turn it into a cause and effect. Must I repeat again the correlation does not prove a causes be. Perhaps it is the social ills that cause the income inequality and not the other way around.

I have to comment on one more graph in the article. This one is titled “Top Marginal Tax Rate” and is accompanied with the statement “And the tax rate on the richest Americans has dropped considerably.” The graph shows as 91% marginal tax rate around 1960 and a current marginal tax rate of 31%. Again data is missing. An important component of discussion here is who is paying those rates. I very much prefer the graphic over at taxcut.org that shows the marginal tax rate by the percentile of the earners income. Here, for example we see that the marginal rate for the 99th percentile peaked at about 53% around 1979 and has now dropped to about 33%. While for the 90th percentile it peaked at about 33% in the mid 1980s and has now dropped to about 25%.

Let me stop there. The article fails many tests of statistical literacy. That is a real shame. The piece makes some good points that are worth thinking about. I can only wish that articles such as this would get a good statistical review before they are published.