Subscribe to Blog via Email

Good Stats Bad Stats

Search Text

May 2025 S M T W T F S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 -

Recent Posts

Good Stats Bad Stats

goodstatsbadstats.com

How Not to Show a Growth in Income Inequality

The Internal Revenue Service(IRS) recently released a preliminary report on the taxes and income for 2010. CNN took the data from this report in conjunction with the same report from the IRS for 2009 to analyze the growth in income inequality in a report titled “Income goes up…especially for the rich.”

The report contains statements such as “Taxpayers earning more than $250,000 saw their total adjusted gross incomes rise by 13.8%, while those bringing home between $200K and $250K enjoyed a 6.7% increase, according to a CNNMoney analysis.”

Unfortunately the analysis of the data is more complicated than just calculating the simple ratio of numbers like CNN did. In 2009 the adjusted gross income for those earning more than $250,000 did go up by 13.8%. However the number of returns with incomes above $250,000 went up 9.6%. Because of this the per return increase in income was only up 3.8%. That is a vastly different number and is the appropriate way to to analyze the data. It provides a much better indicator of what is happening in the economy. CNN goes on to cite an increase of 6.7% in the adjusted gross income for those making $200,000 to $250,000. But there was also an increase in the number of returns in that group as well. As a consequence the grown in the adjusted gross income for that group was only 0.1%.

Those numbers are not anywhere near the 13.8% and the the 6.7% numbers cited by CNN. The error is in oversimplifying the analysis and failing to consider the full situation reflecting both the growth in income and the growth in the population. The two must be taken as a pair in any analysis of this type.

There is a second significant problem with this type of analysis. The upper interval is open ended. Thus the growth in this interval is unconstrained. All the other intervals are what would be called a closed intervals. They have both a lower and an upper bound on income. With all there are people moving both into and out of the various cells. As the economy improves the upper income cell will tend, with a growing economy, to grow in the relative number of people in the cell and the income levels will grow as well pushing up the average income level in that cell. Thus the AGI per return will generally increase as the economy improves. In the middle income cells the predominant movement will be people lower income levels moving into the cell and others will move out of the cell as their income increases. But the overall average income will tend to be stable and move mostly as a result of the shift in the overall income distribution. This is because the income level for the cell is constrained at both ends. But even that is somewhat of a generalization because the true impact will depend on where on the income distribution the cell falls.

Posted in Methodolgy Issues

Graphic Visualization 101

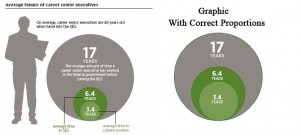

In my last post I talked about the report from the Partnership for Public Service. Today I want to look at just one of the data visualizations in the report as it is a textbook example of how not to present data. The report presents some of the data that I talked about in that last post in what look like a nice fancy graphic image. It shows only three number in what I would call a bubble chart. Each circle represents a separate number. The general rule in graphic visualization is that the area of the graph should be proportionate the to area shown. However in this figure the diameter of the circle was used instead. As result a number that is twice as big shows four times the area. As a result the data visualization is a misrepresentation of the true difference. I have redone the image using the area instead of the diameter of the circles to illustrate the differences. The original graph and the revised graph as shown side by side below.

However I do not like even the revised image as placement of each circle on top of the other hides the true proportions.

This is a case in which a simple old fashioned bar chart would be much more effect.

Posted in Methodolgy Issues

SES Mobility

The Partnership for Public Service in conjunction with McKinsey & Company issued a report this week on mobility within the Government’s Senior Executive Service. The Senior Executive Service is the core of people who manage the many agencies of the Federal Government in the United States. The primary thesis of the report “Mission-Driven Mobility: Strengthening Our Government Through a Mobile Leadership Corps” is that there is not enough mobility within the SES. The original vision for the SES when it was created in 1979 under President Carter wa a flexible and mobile management group.

As I read the report and the some of the media coverage of the report I fail to see how the report makes the case that there is a problem. I am not saying that they are incorrect in their assessment of the situation. Rather I am saying they have not done the analysis necessary to demonstrate their claim.

The key figure that drives their conclusion and which has shown up in the media reports is on the right. Here we see that 45% of the current members of the SES have never held a second SES position during their career in the Federal Government. The claim of the report is that this is a problem. But is it?

To answer this question it is useful to look at some of the other data in the report. On further reading we see that among current members of the SES:

-

3.4 years is the average time they have spent in their current position and

6.4 years is the average time they have spent in the SES.

But who are these people? Remember that the universe is all current members of the SES. That includes those who have just entered the SES as well as those who have been in the SES for a number of years. Consider those who have been in the SES less than a year. Certainly one would expect those people to have occupied only one position during that first year. This group would be part of the 48% who have never changed positions. The key question then is how long should a new member be in the SES before one would expect them to rotate to a new position. This is essential information needed to decide if the 48% figure is too high or is too low. It is not an easy question to answer and there will always be disagreements on what is the best answer. To further complicate the issue the answer will vary by agency and by position with an agency. However without this consideration the 48% figure provides no real useful information.

That is only the first question that must be considered. The entire analysis is much more complicated than it seems at first glance. Basic to the analysis is that this is a case of trying present results using simple means when what is needed is the distribution of the statistics involved. I want to see a table of the number of SES members by years of service cross tabulated by the number of moves they have made within the SES. But even that data has it shortcomings as some of the moves are simply promotions to higher level positions within an agency. It is not at all clear how those changes in positions should be viewed. So even this tabulation needs to be further broken down by the type of move involved for each SES member.

An additional problem with using just the means is that the data is a right truncated. We do not have data on what happens to these members later in their careers. They may just have not yet switched positions yet. The cross tabulation I suggested above would help to alleviate that problem. Otherwise using the mean is like calculating life expectancy by calculating the average age of those still living. I believe that would give us a number in the low 30s.

Posted in Don't Use the Mean