Subscribe to Blog via Email

Good Stats Bad Stats

Search Text

April 2025 S M T W T F S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 -

Recent Posts

Good Stats Bad Stats

goodstatsbadstats.com

Are you better off now?

In the current political campaigns the issue of how are you doing now as compared to when Obama took office has become a recurring question. But how does one answer the question. By its very nature it is a very personal question. It does not ask is the nation better off? It does not ask is the county better off? It very specifically asks if you are better off. Some have said that is a selfish question as John Kennedy said in his inaugural address in 1961: “Ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country”

I watched a television commercial where the question was asked, and then Obama was next criticized for jobs that the candidate claimed he would eliminate in the future. That does not begin to answer the question. Next the commercial criticize Obama for the drop in housing prices. That decline started six months before Obama took office.

Two days ago Robert Samuelson addressed the question more directly in an opinion piece that I saw in the Washington Post. He turned to real data on the economy. His discussion seemed a bit more evenhanded than did the television commercial I had seen. But even there he failed on several points. He also showed a better grasp of the scope of the question starting by saying: “Are you better off than you were four years ago? It’s a harder question than you might think.”

The problem that Samuelson had was that he dealt with data the focused on the economy as a whole rather than on the individual. His focus was not really on “are you better off?” but rather “is the country better off?” The data he used were:

- Jobs,

- Unemployment rate,

- Disposable per capital income adjusted for inflation,

- Average hourly earning,

- Inflation,

- Price of as,

- Dow Jones average,

- and Consumer confidence.

The first two variables are Jobs and Unemployment. It purports to measure if I am better off in terms of employment. The actual number of jobs and the actual unemployment rate are of little practical significance here to any one individual. They become important if I work in sales and cannot earn the income I used to earn because others do not have the income to buy a new car or other item. They are important if I am a business man and cannot sell the products I am producing. But my income and situation does not change if I am an auto worker on the assembly line of if I work minimum wage sweeping floors. But they are all income related components and would be better evaluated by looking at my level of income and how it has changed over time.

One might think that disposable income would be a good measure. But it has to reflect the change in my disposable income, not an average for the nation as Samuelson has used. A change in the average does very little to show what is going on at the level of the individual This is shown very clearly in the discussions of the changes in income inequality. While incomes have gone up over the last 30 years the level of income inequality has also increase. So those at the top of the income scale have benefited disproportional and thus would be likely to say they are better off now many, and perhaps most, would say that even though the average has gone up they are not any better off.

When I shifted to a 30 year time span in my discussion of incomes I touched on a problem with the types of numbers Samuelson uses. That is that the people in the groups change over time. The recent college graduate who is not working in the field of his choice may well be better off in that he is making much more money than he was while in college. He may not feel real good about that if it took him a year to find the job. To him the question is not “am I better off? But rather “am I where I want to be?”

Then there is the level of the Dow Jones that Samuelson cites. This is only relevant to those impacted by the stock market. Many will see neither a gain nor loss as the value of the stock market change. The key problem here is that he uses the wrong data points. He failed to show the entire picture of what has happened over the last five years. Samuelson shows that he understands this when he says: “The stock market’s gain, although real, is misleading.” If that data he is showing is misleading and he knows that then why does he show it and second why does he not pick more appropriate data to make his point? The usual advice to investors is it to expect ups and downs in the stock market. For those who don’t need their money now this is a blimp in the time series. Taking a step further, for those who rely on their stock portfolios the drop in the stock market can well be a disaster. Each individual case is different.

One of the worst statistics that Samuelson cites is the price of gasoline. The problem here is the same as with his use of the stock market data. While his numbers are correct. The price of gas was $1.79 a gallon when Obama took office. But the prior summer before the economic collapse it was close to $4.00 a gallon. So to show numbers that demonstrate the price of gas has increased 107% since Obama took office is only providing a good example of how to lie with statistics. It should be clear to all that the expectation should have been that once the economy recovered the price of gas would return to precession levels. So a current price of $3.72 per gallon should be a surprise to no one and a criticism of no one.

His conclusion thought hits the nail on the head. The real question is “The rap against Obama is that he hasn’t repaired the damage fast enough.” But beyond that there is remains the fundamental philosophical differences between the parties on how government does or does not interact with the economic factors at work in the world.

Fooled by Randomness: Earthquakes and Suicides

The Chief Coroner in Christchurch seems to think there is a good chance of a link between earthquakes and suicide rates. As I look at the plot of the number of suicides by month over the last five years the data looks like nothing but random variations. And in fact Luis Apiolaza over at Quantum Forest has done a good job of showing just that. A few simulations based on the variation in the actual data shows rather clearly that the kinds of variation that has been observed.

Posted in Uncategorized

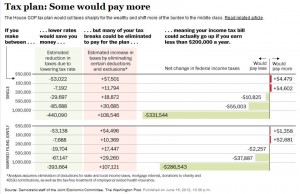

GOP Tax Plan – How to Confuse Your Readers

I spotted the graph to the right in the Washington Post yesterday. Click on the image to obtain a larger, clearer image. The article dealt with the impact of the GOP tax cuts on the middle class and was based on a report by Senate Democrats and their assessment of the tax plan put forth by the Ryan.

I spotted the graph to the right in the Washington Post yesterday. Click on the image to obtain a larger, clearer image. The article dealt with the impact of the GOP tax cuts on the middle class and was based on a report by Senate Democrats and their assessment of the tax plan put forth by the Ryan.

The graph fails to communicate on several levels. The most basic issue is the lack of context for the numbers in the graph and and adequate base for the various income levels. Particular troublesome is the lack of a base for those making over a million dollars. Is the decrease in taxes for married couples with an average income of two million, three million, ten million. The impact of the decrease of $286,000 dollars in taxes is very different depending on the income levels in the group. Open ended categories like the one used here rarely work well either in a graph or in a table.

The second piece of useful information missing is the current tax liability for the groups shown in the table. What is the relative increase or decrease in taxes paid under the plan would be valuable information to have. While singles making between one and two hundred thousand dollars would “on average” pay an additional $4,600 in taxes and no one want a new bill of that size to enter into their expenses such numbers need to be put in the context of the taxes they are already paying. Is this a doubling of their tax bill or is it a ten percent increase?

Posted in Uncategorized